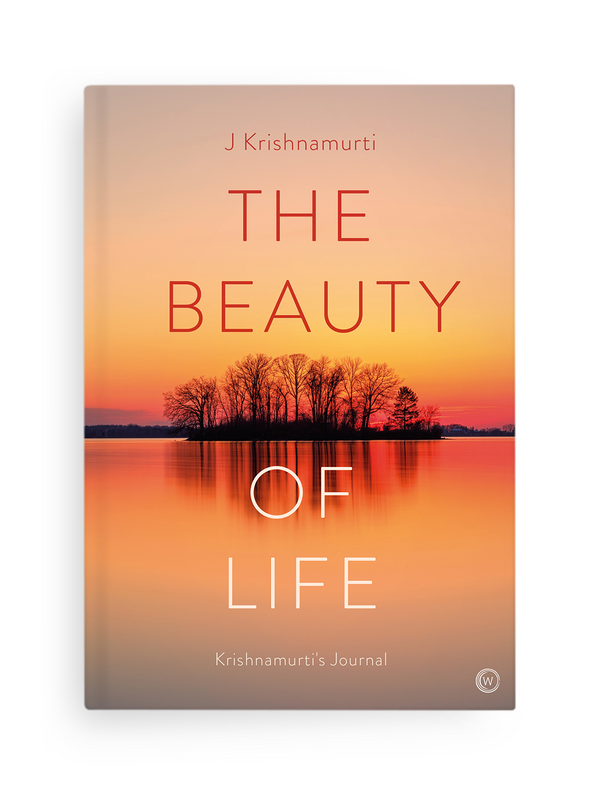

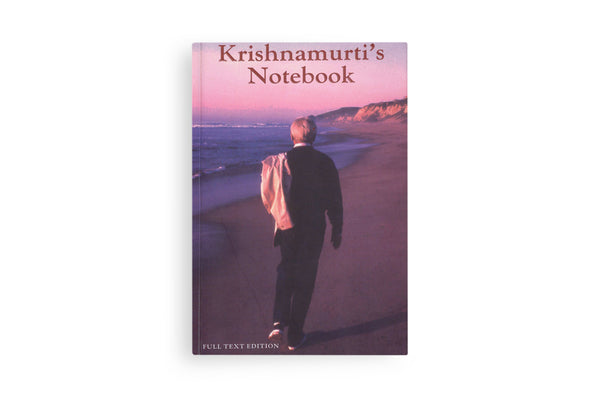

In this unique volume Krishnamurti lets us into the private world of his states of consciousness. Written as a diary, detailing his travels, the day-by-day account moves with breathtaking swiftness from the sights and sounds of his immediate environment to those moments of bliss variously described as “immensity,” “benediction,” or “the otherness.” We are also privy to what Krishnamurti calls “the process.”

From the book:

Meditation, in the still hours of early morning, with no car rattling by, was the unfolding of beauty. It was not thought exploring with its limited capacity nor the sensitivity of feeling; it was not any outward or inward substance which was expressing itself; it was not the movement of time, for the brain was still. It was total negation of everything known, not a reaction but a denial that had no cause; it was a movement in complete freedom, a movement that had no direction and dimension; in that movement there was boundless energy whose very essence was stillness. Its action was total inaction and the essence of that inaction is freedom. There was great bliss, a great ecstasy that perished at the touch of thought.

The sun was setting in great clouds of colour behind the Roman hills; they were brilliant, splashed across the sky and the whole earth was made splendid, even the telegraph poles and the endless rows of building. It was soon becoming dark and the car was going fast. The hills faded and the country became flat. To look with thought and to look without thought are two different things. To look at those trees by the roadside and the buildings across the dry fields with thought, keeps the brain tied to its own moorings of time, experience, memory; the machinery of thought is working endlessly, without rest, without freshness; the brain is made dull, insensitive, without the power of recuperation. It is everlastingly responding to challenge and its response is inadequate and not fresh. To look with thought keeps the brain in the groove of habit and recognition; it becomes tired and sluggish; it lives within the narrow limitations of its own making. It is never free. This freedom takes place when thought is not looking; to look without thought does not mean a blank observation, absence in distraction. When thought does not look, then there is only observation, without the mechanical process of recognition and comparison, justification and condemnation; this seeing does not fatigue the brain for all mechanical processes of time have stopped. Through complete rest the brain is made fresh, to respond without reaction, to live without deterioration, to die without the torture of problems. To look without thought is to see without the interference of time, knowledge and conflict. This freedom to see is not a reaction; all reactions have causes; to look without reaction is not indifference, aloofness, a cold-blooded withdrawal. To see without the mechanism of thought is total seeing, without particularization and division, which does not mean that there is not separation and dissimilarity. The tree does not become a house or the house a tree. Seeing without thought does not put the brain to sleep; on the contrary, it is fully awake, attentive, without friction and pain.

Attention without the borders of time is the flowering of meditation.

Customer Reviews

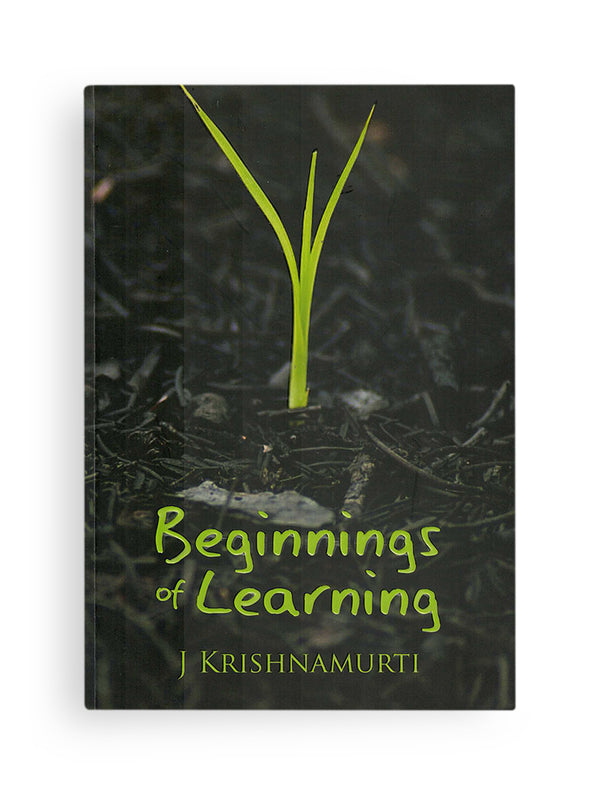

Jiddu Krishnamurti lived from 1895 to 1986, and is regarded as one of the greatest philosophical and spiritual figures of the twentieth century. Krishnamurti claimed no allegiance to any caste, nationality or religion and was bound by no tradition. His purpose was to set humankind unconditionally free from the destructive limitations of conditioned mind. For nearly sixty years he traveled the world and spoke spontaneously to large audiences until the end of his life in 1986 at the age of ninety. He had no permanent home, but when not traveling, he often stayed in Ojai, California, Brockwood Park, England, and in Chennai, India. In his talks, he pointed out to people the need to transform themselves through self knowledge, by being aware of the subtleties of their thoughts and feelings in daily life, and how this movement can be observed through the mirror of relationship.